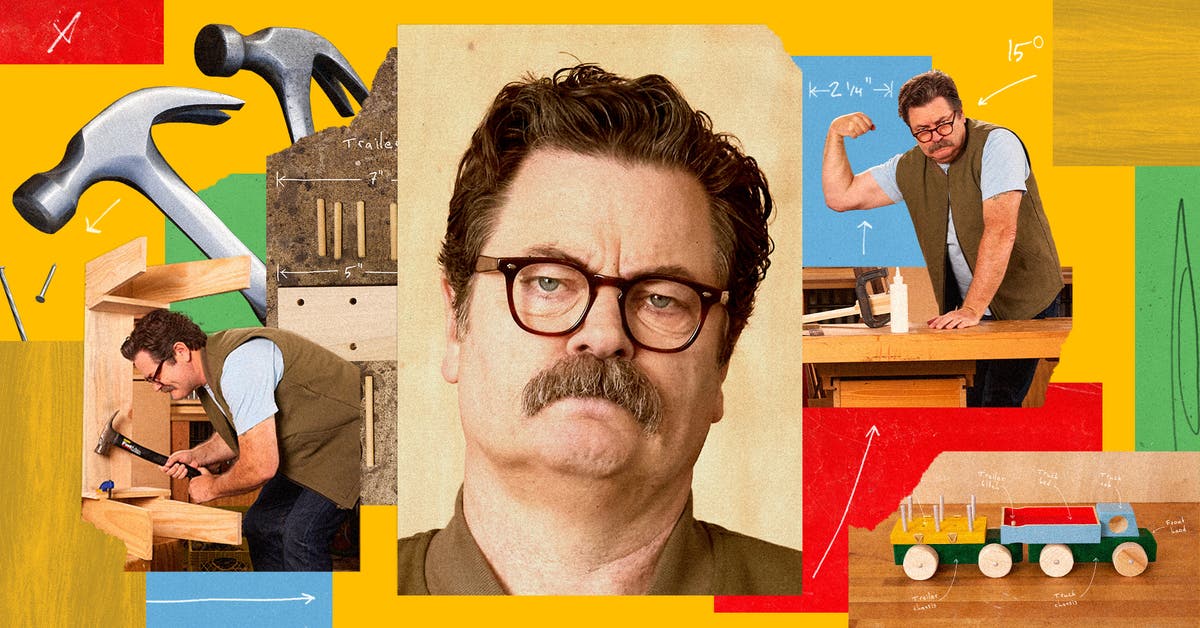

Nick Offerman Told Me That Swinging a Hammer Might Change My Life

“When you drive a nail successfully, you feel like an absolute superhero. It’s incredible.”

This is Nick Offerman delivering an endearingly earnest sermon, over videoconference, about a hammer — an Estwing, to be exact, but we’ll get to that. We’re chatting on the occasion of his latest book, Little Woodchucks: Offerman Woodshop’s Guide to Tools and Tomfoolery, a family-friendly manual for building things like your own toys, a toolbox, or one of those little free libraries. To hear him talk about it, though, maybe the book is also a manifesto about how an implement as humble as a hammer can actually change your life.

“We’ve been taught to live in a way that you don’t ever get dirty,” he says, “[but] working with my hands has made my life successful and really incredibly gratifying.”

Offerman is both a professional woodworker and a deeply beloved character actor. His most memorable roles (Ron Swanson in Parks and Recreation, Bill in The Last of Us) have shared his fanaticism for DIY, self-reliant craftsmanship. If you already know those two things about Offerman, then you’re likely not surprised by any of this. He probably waxes rhapsodic on hammers all the time, not just when he’s scheduled to talk to a reporter about them over Zoom.

“There are a wonderful selection of hammers in the world,” he says in his avuncular baritone, “from tiny cobbler’s hammers that are made to hammer tiny nails into shoes, all the way up to giant sledgehammers and framing mallets that are like what a circus roustabout would use to drive giant stakes to put up the big top.”

But of all the hammers in all the land, he tells me, “The default hammer is the claw hammer.”

Indeed, a claw hammer is what you likely picture in your mind when you think of a hammer: On one side of its head is a flat, circular surface for pounding nails (the face), and opposite that is a curved, two-pronged fork (the claw) for pulling them.

Not only are claw hammers relatively lightweight (generally 12 to 16 ounces), but they’re also well suited for a wide array of DIY projects and household tasks. In Offerman’s words, “If you’re gonna put together your household tool kit, the claw hammer is where you wanna start.”

For a neophyte like me, whose regard of hammers begins and ends with the occasional need to hang a picture, he suggests nonjudgmentally that I may be “missing out on the joy and comfort of living a self-sustainable life” due to my lack of hammer familiarity.

“Everyone,” he says as if addressing his employees in Pawnee, “needs to be reminded how to hammer and nail.”

What he’s getting at, I think, is that a hammer isn’t something to stash on a pegboard somewhere just in case. It’s an opportunity for so much more. (“Man, if you have the wherewithal to do something like a tree house or a deck …” he gushes at one point, before segueing into a screed against automation: “Construction sites now are festooned with pneumatic nail guns … I hate working with them.”)

So when he tells me, “Get yourself a hammer. Just a normal hammer … just a little claw hammer,” I immediately think, “Definitely.”

I mean, maybe Nick Offerman is just talking in hypotheticals, but at that moment, I fully commit. I am definitely going to get a claw hammer, learn how to swing it, and experience the sublime satisfaction of a well-driven nail. Then I’ll probably pull a Thoreau and go to the woods to live deliberately and to blast that Peter, Paul and Mary song on repeat. I think Nick Offerman would be proud of me if I did.

Before I can ask him which claw hammer, he tells me: “Estwing is a great brand.”

Top pick

Manufactured in Rockford, Illinois, since 1923, an Estwing hammer is a thing that many, if not most, handypeople are likely to know and appreciate — perhaps even adore. Their claw hammers are forged from a single piece of Nebraska-sourced steel and sold with a choice of two handle-sheathing grips: either a rubbery blue “shock reduction” grip (which we recommend) or a leather grip for a more refined look. Its 16-ounce claw hammer has been our top-pick hammer for more than a decade.

Offerman came to Estwing’s tools organically. “It’s not like anybody ever paid me to do a tool test or anything,” he says. “I started with an old hammer my dad gave me that his dad gave him, and I still have that in my drawer at the shop.” (Speaking of old hammers, he encourages folks to shop for used hammers in person or online, because several vintage, American-made brands were built to last.)

I learned after our chat that in 2019, Offerman replied to a Twitter follower’s request for a hammer recommendation by sharing our guide to the best hammers and writing, “I love my Estwing … I’m tickled to see these professional nailers agree.”

In that guide, we call Estwing hammers “a favorite of carpenters everywhere … because they deliver everything you could want in a hammer.” In addition to naming its 16-ounce claw hammer our top pick, we also recommend its 12-ounce claw hammer, which we deem “best for light-duty work,” and its 20-ounce rip claw, which boasts a straighter claw designed for demolition and is “best for bolder DIY jobs.”

Best for…

“It’s a very charismatic design,” Offerman says about the Estwing line. “It’s good-looking, it’s well balanced … It’s a joy to use, everything about it.”

Of course, none of that means it’s completely foolproof. Once I get my hammer, I’m advised that there’s one more thing I should do.

“The most powerful thing you can have is a teacher there in person,” Offerman says. “Having a hands-on teacher just skips you past several mistakes.”

Cut to nine days later. I’m in the backyard at my co-worker Tim Heffernan’s house, standing in front of a pair of sawhorses with scrap wood laid across them, Estwing in hand. I’ve taken Nick Offerman’s advice; I am there to commune with a craftsperson mentor. Tim, a home-improvement writer, is the handiest of journalists; around the Wirecutter office, he’s the guy you go to for advice about anything from water filtration to restoring rusty metal.

“Start your nail by tapping it and learn to feel the leverage of your hammer,” Offerman had told me. “The weight of that hammerhead is what needs to do the work. Your arm doesn’t wanna do the work.”

In person, Tim added that I should hold the hammer as if I’m shaking hands with it, letting the handle nestle between my thumb and forefinger, which will give me more control while causing less fatigue. He also reminded me to drop my hammer straight over top, so that it’s not coming toward the nail at an angle.

Offerman had said that I will have a moment when I realize, “All I needed was to be coached through this.”

As I start hammering, I get it.

Sure, some of my nail heads wind up crooked, and compared with Tim, it takes me way more swings of the hammer to drive a nail all the way into the wood. Tim reminds me, though, that we both end up with nicely driven nails. Our journeys may not have exactly mirrored each other, but we arrived at the same destination.

We spend hours doing only this, just hammering nails into wood. Offerman told me that it would be “a blast,” and it is. I try both the 12-ounce and the 16-ounce Estwing hammers. It’s a slight difference, but I prefer the latter; the bit of extra weight seems to help me drive the hammer more assuredly, with less wobbling on its path toward the nail head. I feel so energized. I want to call a friend and ask them to come over and have a beer and hammer some nails with me. I truly want to hammer nails all day long. In the morning, in the evening, all over this land.

A few weeks later, I haven’t swung a hammer since, but I am certain that I will — and that it will, obviously, be my new Estwing hammer. I’ve discovered something inside me that I didn’t know was there before: an adventure I want to embark on again, perhaps a latent skill to further explore.

After all, as Offerman told me, “Everybody has an art, and you’ve got to figure out what it is. Some of us might be woodworking, some of us might be making lasagna, some of us might be programming AI. It covers the whole spectrum of human creation. But you’re supposed to — you know, in a religious sense — you’re supposed to understand your gift that nature has given you and then service your fellow humans with that gift.”

“That’s kind of, I think, the holiest way one can live.”

Preach.

This article was edited by Katie Okamoto and Catherine Kast.